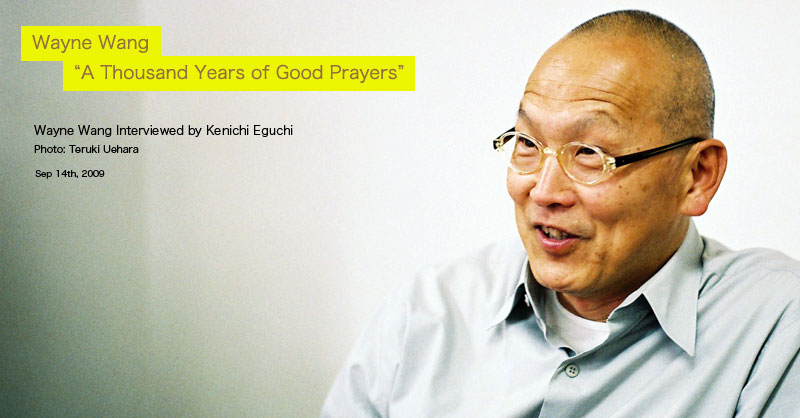

Wayne Wang is still known for his films “Smoke” “Blue In the Face” and the “Center of the World”, in which he collaborated with the noted Brooklyn writer Paul Auster. But he was already known as an excellent filmmaker, after his second film “Chan Is Missing” caught attention, as a sincere film director who can tell Chinese based stories. With the impression as someone who can make good literary stories into films, and his well balanced choices from independent to Hollywood studio productions, he went to direct bigger budget films such as “Anywhere But Here” and “Maid In Manhattan”. But still people were longing for his emotional literary films where he tells a good story. Hence the film some of us have been waiting for. He goes back to his Chinese heritage to film “A Thousand Years of Good Prayers”, based on a short story by bestselling writer Yiyun Li. He again asked the author to write the screenplay. The film was acclaimed by many, and won many awards including the festivals in San Sebastian and Locarno. Maintaining a minimal and simple storytelling, he tells the story of a father, visiting his daughter in the States. Although they are family, they have ended up living two separate lives in different countries and background, speaking different languages, and coming from two different generations divided by the Culture Movement in China. By focusing on the relationship between the father and daughter, he tells a universal story that can be understood in many cultures. The director was far from being stern, and answered my questions in good humor, always ending in a friendly laugh. Throughout the conversation, his sincerity shows, as you can tell how he tells a good story.

Outside In Tokyo: This film “A Thousand Years of Good Prayers” was filmed in 2007, was it released the same year?

Wayne Wang: It was filmed in 2007, and was taken to festivals, so it was in (the festival at) San Sebastian in 2008.

And you received awards there?

Yes! It got best film, and best director and best actor! We got everything, actually (laughs).

How does this film fit in, within the time in your career, in your filmography?

I’ve done so many different things, because I feel I’m not one thing as a person. I am a Chinese born in Hong Kong, which used to be a British Colony. I was educated by Irish Jesuits. Then I went to America. I love American music (laughs)! So I’m kind of a weird collision between cultures anyway. So that’s why I wanted the film to be; a lot of different things. Chinese things, obviously, which I know well. I started my career there, but I did many different things. But this is the first one I’m going back to, to the Chinese in America, because I know it so well. And I read this story by Yiyun Li. And I really have personal connections to it. I have a very different relationship with my father. I went to America. And I became a different person. English became my predominant language. So there were a lot of things that kind of connected with my own life. In an odd way, I’m like Yilan in the film!

When I first read articles about the film in the states, I thought ‘this’ is definitely a Wayne Wang film. But at the same time, you don’t seem to differentiate from the bigger budget films to the more independent. When you say different, how different are they?

It’s very different. For example, in the big budget films, you are never allowed to breathe. The film doesn’t breathe. Everything is cut very, very fast. When nothing happens, it’s gone. So this film really, well, first of all, kind of gives you time to breathe. And in this way, I’m a big Ozu admirer. I think there are lots of references to his films. So that’s one. Two, it doesn’t have a big dramatic story. It doesn’t have your Hollywood, Act 1, Act 2 and Act 3. It’s shot very simply. It doesn’t have a lot of what’s called coverage (shots). There are almost no close ups until maybe towards the end. It’s all very observational, which is something that’s quite Asian in a sense. You don’t get inside things too closely. You watch it. If you look at films by Ozu, who is the master of that (you will see that). If you look at Hou Hsiao-hsien, and even somebody earlier like Zhang Yimou, when he made character driven films. They were all like that, with that kind of aesthetic. So in that sense, if you compare it to the bigger films, it’s very different. I also like the fact that, that it’s very simple and yet very complicated. It seems like nothing happens. It seems like the camera doesn’t move. It seems so simple. But there’s a lot. I like that. I mean, I started out as a painter in my career. And by the end of my painting (days), I was pretty much just working with maybe one color, with a lot of texture, and things like that. I stripped away everything. So in that sense, it’s also quite different.

Can you tell me more about the reference to Ozu?

I think, when I was going to film school, he was the one director that gave me a sense of what Asian aesthetic might be. Because film is a western language, film is a Hollywood language, but Ozu took it and found a way to express it in a very Japanese way. The camera angle it is at, and the timing of his shots. It is the observational quality I was talking about. And the other thing that I really like, is the fact that he always had these, it is what Donald Ritchie had in his book called the pillow shots, or empty shots, of the environment. Sometimes, he will just have a hallway. Nobody is in it, and nothing happens. But it is the environment that contains the emotions of everything that has gone on within the family or in the story. And that is very Asian, because Americans or Westerners don’t see the environment as part of the story. The environment just happens to be there and it’s the background. Asians are very conscious about the environment. It’s so much a part of you, and what happens. So, those were the things that hit me strongly when I was a film student. And I made an earlier film called “Dim Sum” which used some of those things. And I think this film was more, maybe refined, in those things. Because I have been thinking about them a lot. So I think, in a way, it’s a very good film that pays respect to somebody like Ozu.